This article provides an overview of injectable rejuvenation of the facial lower third, specifically the chin. After defining the chin, we will discuss its uniqueness in humans, sexual dimorphism, manifestations of aging, and finally how to stage injectable treatment to optimise aesthetic outcomes.

Facial injectable treatment, like any other endeavor, begins with the end in mind. Unlike purely therapeutic treatments, aesthetic procedures have to satisfy both the practitioner and the patient.

To achieve this, cosmetic consultations must include the following:

- What are the treatment goals?

- What does success look like in the treatment area?

- Can treatment goals be achieved with injectables?

- Will the patient be satisfied with the projected outcome?

As obvious as these considerations may seem, treatment results that miss the mark are often the consequence of not thinking through the goals of the patient, and the intentions of the practitioner before the first needle is uncapped. This means that success is often doomed from the start.

In all areas of the face, practitioners need to have a clear and uniform vision of what the ‘optimum’ result looks like. It sounds straightforward until you realise that ‘optimum’ is predicated on and modified by age and gender.

For example, creating full, plump lips on a 55-year-old man, in general, looks unnatural. This is also why ‘single technique’ practitioners struggle when a patient outside of a specific demographic presents for treatment. Using the same technique on every patient can be a recipe for disaster.

Understanding how age and gender impact the operational approach and goal of any given treatment is an essential skill. Likewise, the ability to convey that information to patients in a clinically compassionate way is also fundamental.

Defining the chin

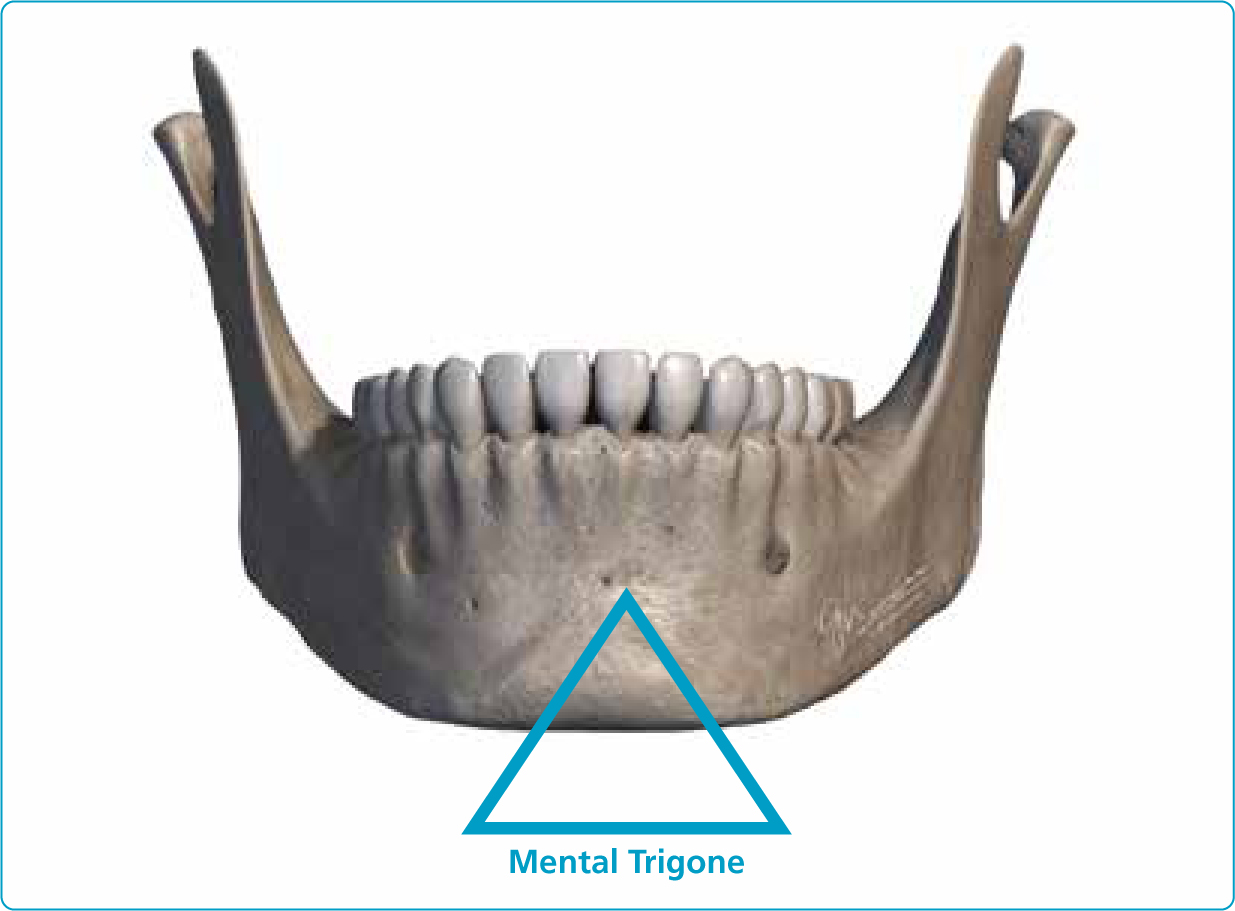

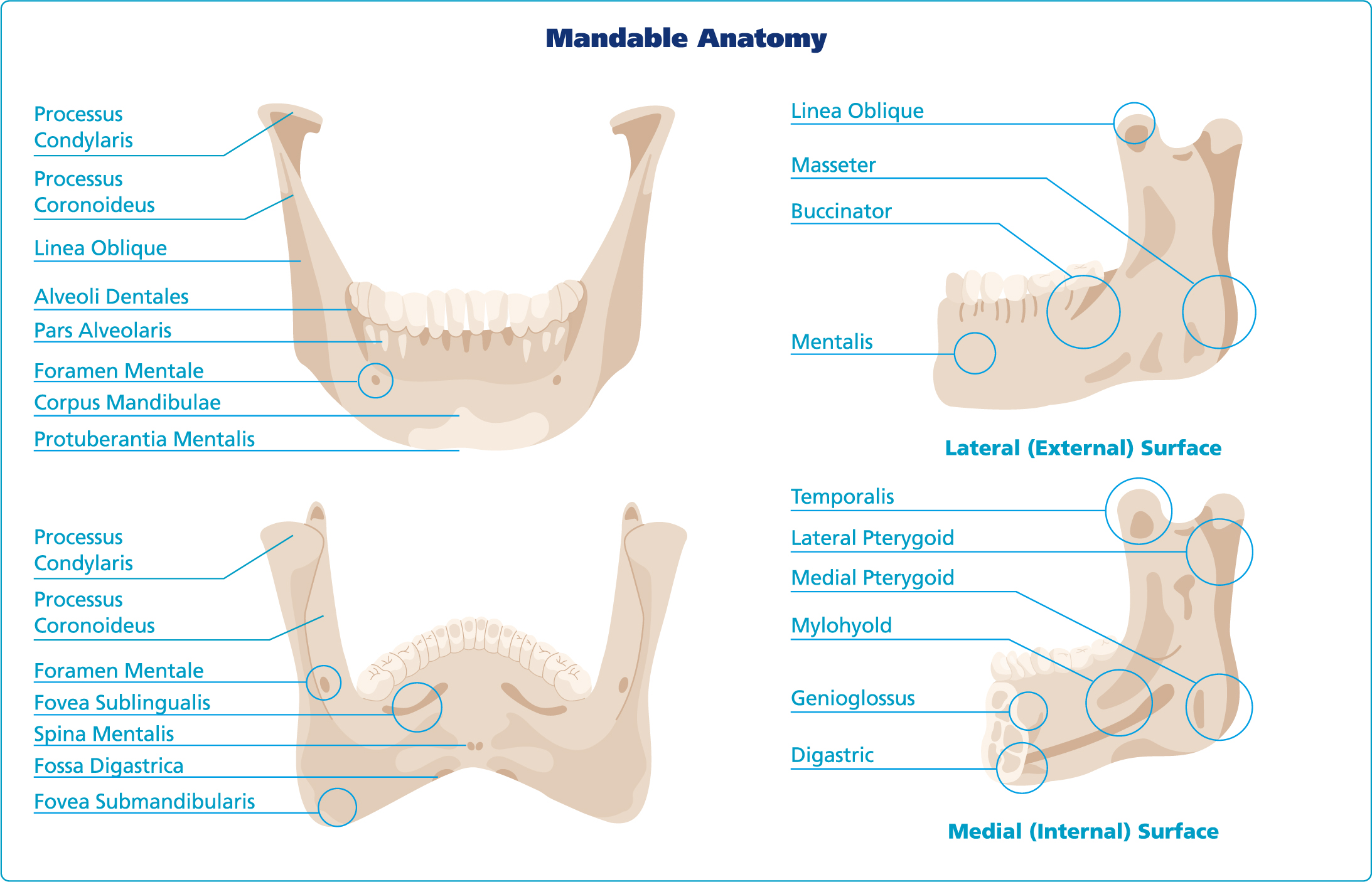

Anatomically, the chin, or ‘Mentum’, is defined as the frontal portion of the mandible, which is the anatomical line of fusion between the two embryologically distinct halves of the mandible (symphysis menti) This fusion line creates a slightly raised median ridge that divides inferiorly to enclose a triangular area called the mental protuberance. This fusion point is not a true symphysis, in that there is no cartilage between the two halves of the mandible. At the midline, the base of this protuberance is depressed and flanked by raised areas known as the mental tubercles. Collectively, the protuberance and the two tubercles are called the mental trigone [fig. 1]. Ideally, the chin projects anteriorly to a point that meets a vertical line drawn from the nasion, which is perpendicular to the Frankfort horizontal line. This point of maximum projection is called the pogonion.

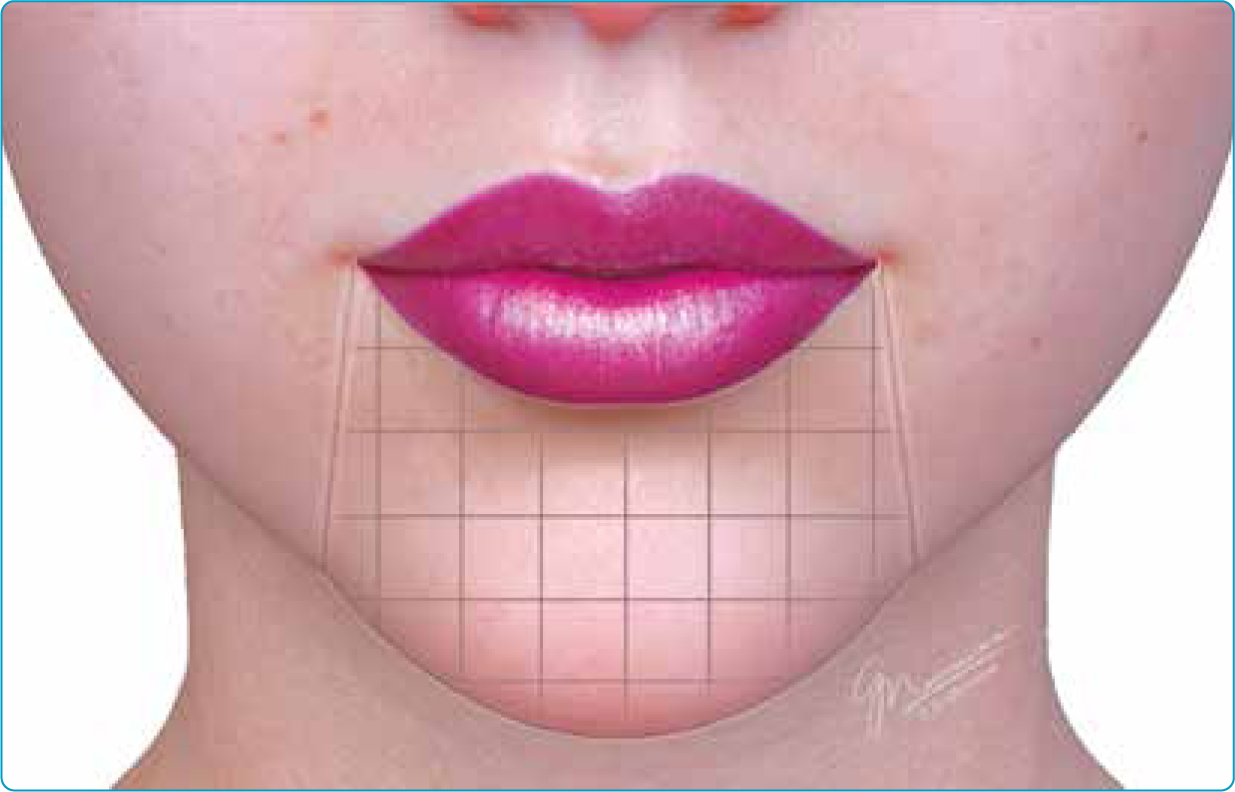

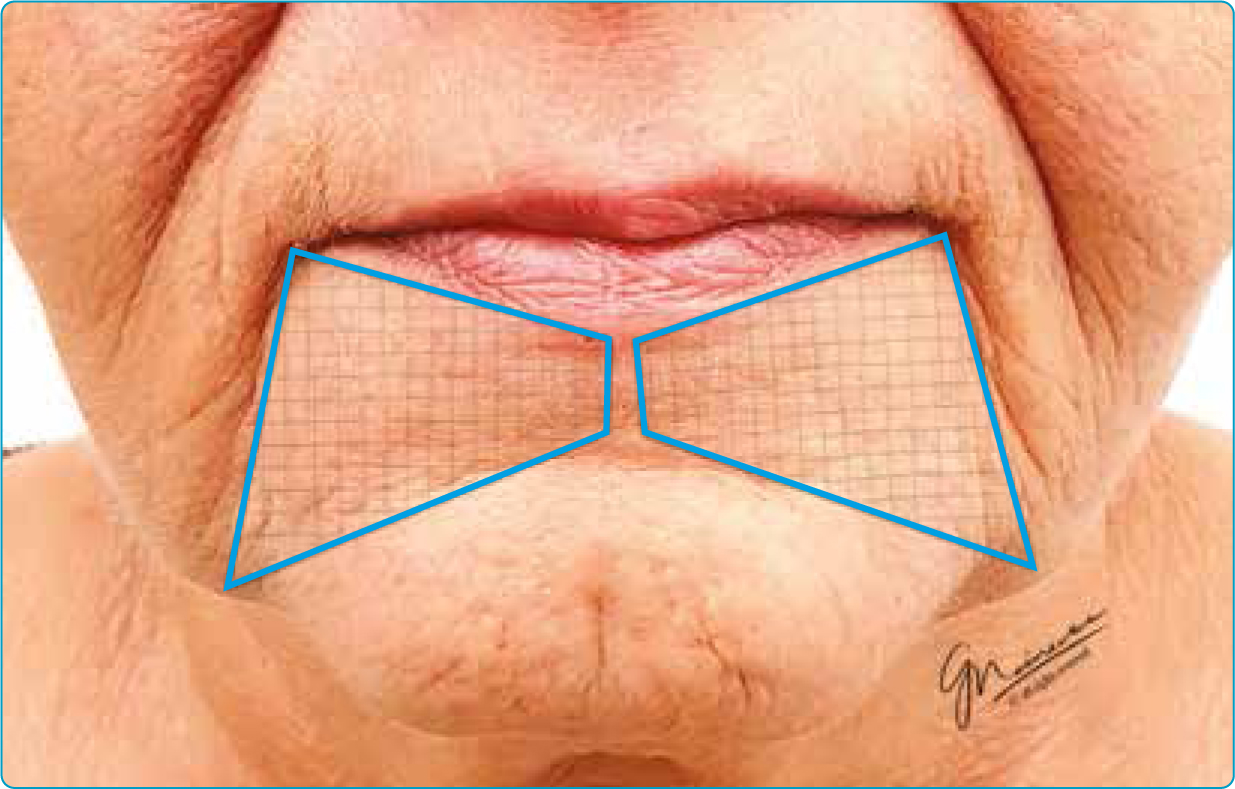

For our discussion, we will define the chin in slightly broader terms. A more inclusive description is suitable since aesthetic treatments typically encompass a region, rather than a single point of projection. Here, we will use the term ‘chin’ to denote the location bound superiorly by the lower lip, laterally by a vertical line dropped inferiorly from the oral commissures (approximating the marionette lines) and defined caudally by the inferior border of the mandible [fig. 2].

Uniqueness of the human chin

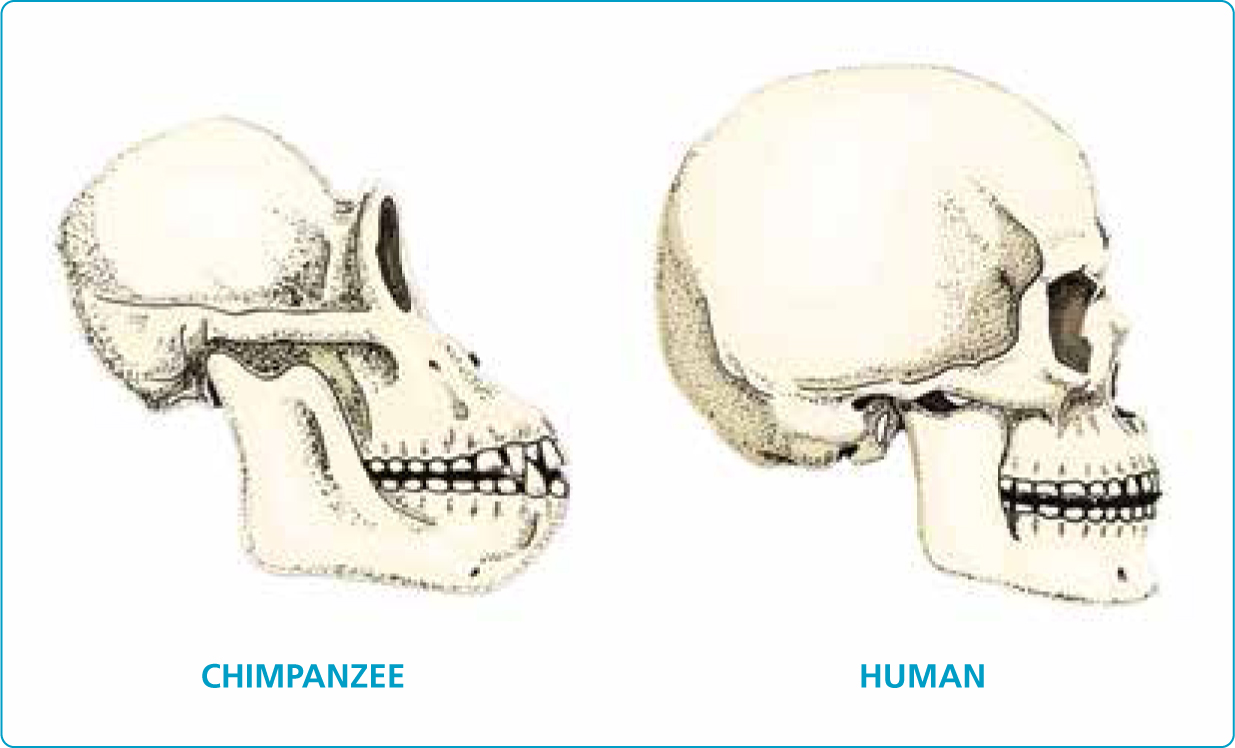

The forward projecting element at the midline of the mandible is a distinctive feature in homosapiens (Schwartz and Tattersall 2000). Very specifically, the triangular-shaped projection, the mental trigone, is uniquely human. All mammals, even our closest DNA relatives, the chimpanzee and the bonobo, lack an anteriorly projected mentum. Their ‘chins’ slope posteriorly in a retrusive fashion [fig. 3].

Much attention has been given to the human chin and the possible reason why humans ‘developed’ that midline mandibular projection. Through the years, evolutionary anthropologists have offered many theories as to why the hominin chin came to be — whether by mutation, genetic drift, gene flow, or natural selection. Some of these theories have been disproven and others have yet to be validated. For example, adaptation hypotheses for both speech and mastication have been negated, since it is extremely likely that chinless extinct hominins used complex vocalisations. Likewise, functional analyses demonstrate that the human mandible is actually overbuilt for the masticatory demands of our modern diet. Moreover, since both men and women have chins, the ‘sexual ornament’ theory is unsupported. The current popular theory is that it is vestigial, and has no functional advantage or purpose (Pampush and Daeling 2016).

Regardless of its evolutionary etiology, the chin significantly contributes to our aesthetic interpretation of the overall facial shape. A well-formed chin creates balance and harmony. To a certain degree, it even plays a role in social signaling. A chin's projection can influence our perception of an individual's dominance, without any evidence to support such an assumption. Its ‘strength’ or ‘weakness’ is often used in first impressions to intuit a person's character or leadership qualities. Notwithstanding the incentive, whether social or structural, consideration of the chin, its size, and shape, are important factors in any facial aesthetic evaluation.

Sexual dimorphism

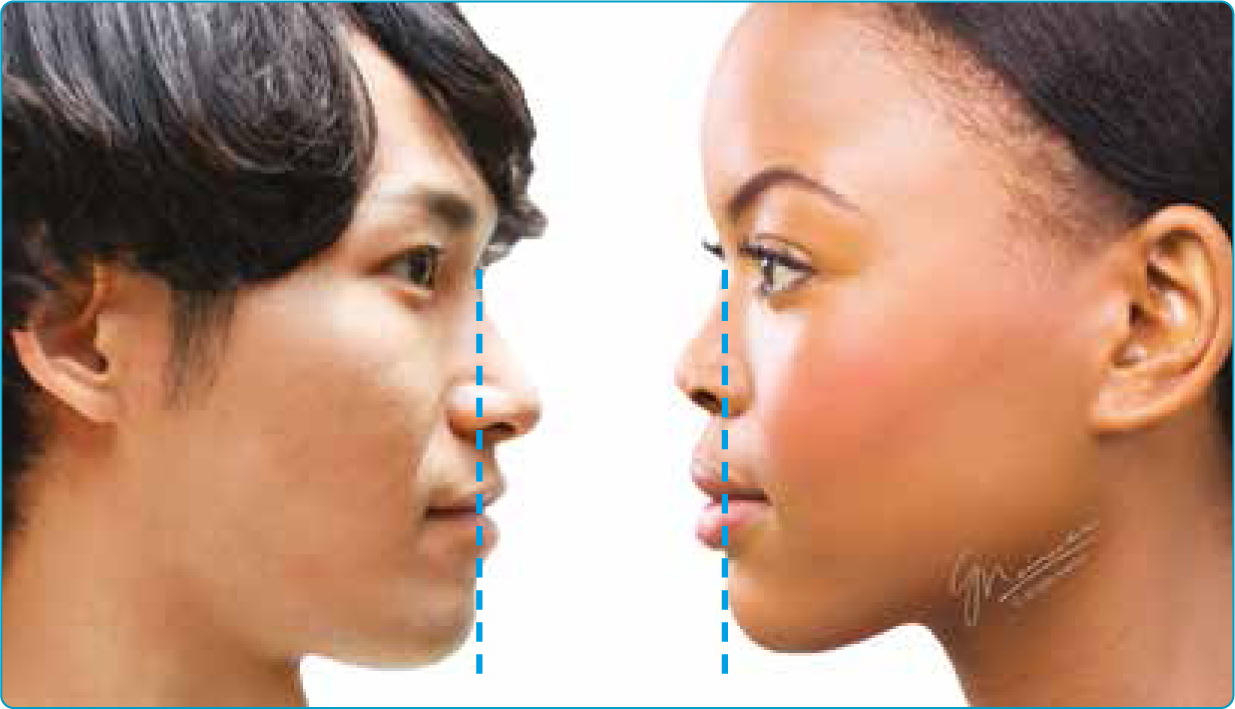

From an aesthetic point of view, regardless of culture or ethnicity, we prefer a chin that projects anteriorly far enough to meet a vertical line coincident with the nasion in both men and women [fig. 4]. However, geometrically, the chin shape does present sexually dimorphic differences. The male chin is one of the most characteristic features of the masculine face. It tends to protrude more, with the lateral tubercles more developed than those of the female, creating a more square and wider appearance (Thayer and Dobson 2010). The female chin appears rounder in shape, with its width approximating the medial intercanthal distance. The anatomical reference for width in men is slightly wider, ending at the oral commissures (Braz and Aduardo 2020).

Optimum chin aesthetics

Without question, the chin is the drum major of the facial lower third. It contributes greatly to overall facial shape as well as providing balance to other facial features. Studies show it is a key factor in facial attractiveness as well as the perception of youthfulness (Naini et al. 2012; Thayer and Dobson 2013). Large disparities in chin height in both men and women are perceived as the least attractive facial feature. Due to the negative impact on a patient's self-image, chin height disproportions are frequently corrected surgically (Naini et al. 2011).

Even today, the majority of injectable practitioners fail to routinely include the chin in aesthetic treatment planning. Moreover, it is rare that a patient possesses the necessary level of knowledge to recognise that their chin has either undergone age-related changes or that injectables can enhance or rejuvenate this area. Practitioners and patients alike, usually zero in on crowd favorites such as lips and cheeks, often overlooking other pivotal structural assets. Treating popular areas such as the lips without considering the chin is akin to replacing only the front door of a dilapidated house.

Senescent chin presentation

Like other facial features, the chin sustains volumetric and topographical changes over time. Age-related hard tissue changes manifest primarily as dimensional and positional modifications. A decrease in the height of the symphysis in both sexes leads to a squarer appearance of the chin shape. Mandibular rotation (posterior in women and anterior in men) leads to a retrusive or protrusive chin appearance respectively (Sella Tunis et al, 2020). In both men and women, the buccal aspect of the bony incisive fossa undergoes age-related resorption. Interestingly, the skeletal thickness of the incisive fossa remains largely unchanged due to concurrent apposition on the lingual aspect in that area (Pessa et al. 2008). Nonetheless, predictable resorption patterns diminish bony scaffolding which, in youth, provides support to the overlying soft tissue flanking the mentalis muscle. Age-related resorption results in a weakening of soft tissue projection in that area.

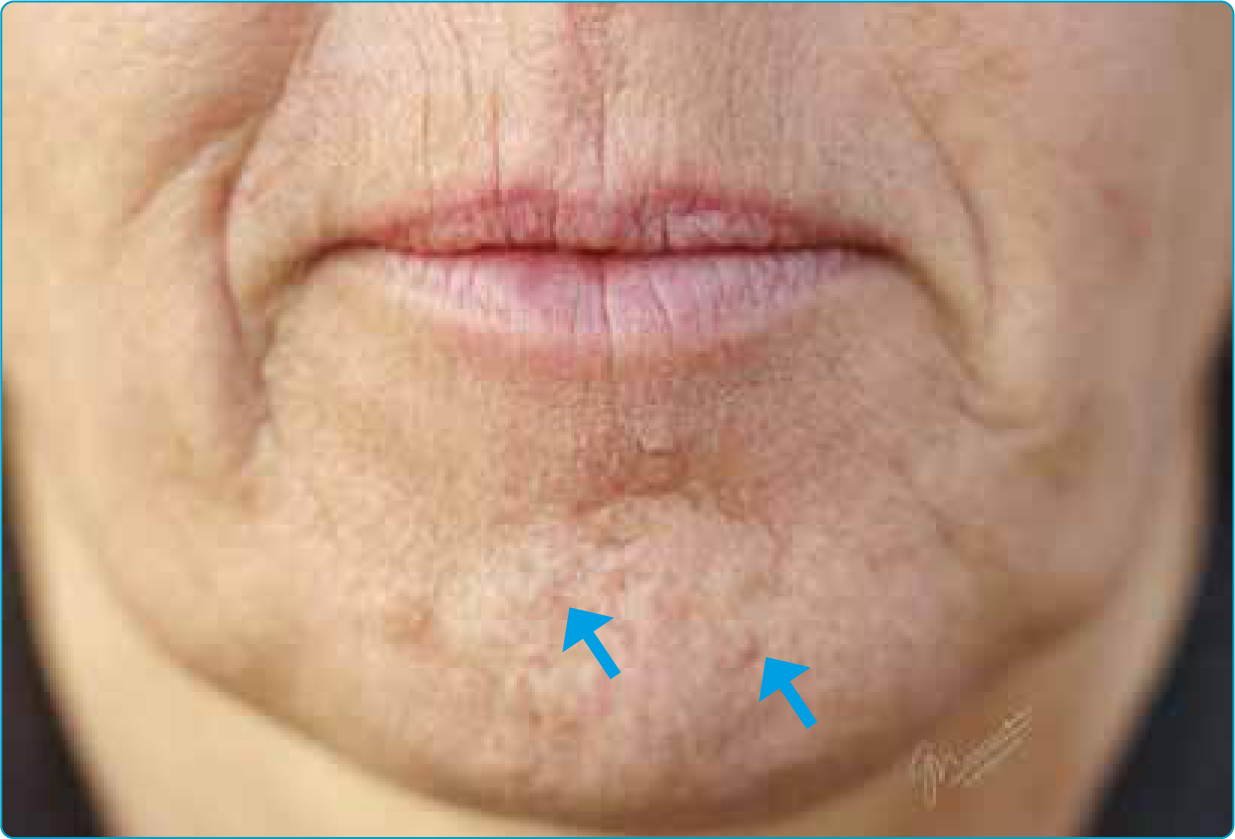

Soft tissue changes in the face begin early in adulthood and are strongly correlated with sun exposure and smoking (Langton et al. 2020; Situm at al. 2010). Facial aging is more noticeable in females than males due in part to differences in skin thickness and collagen content (Lee Y and Hwang K 2002). These changes are precipitated primarily by the hormonal impact of menopause (Fitzmaurice and Maibach 2010). Regardless of sex, age-related soft tissue depletion allows surface irregularities in the facial lower third to become more obvious. Multiple, conspicuous mentalis muscle-skin insertion points become visible. These randomly arranged adhesions between muscle and skin produce an irregular, ‘potato-eye’ appearance [fig. 5].

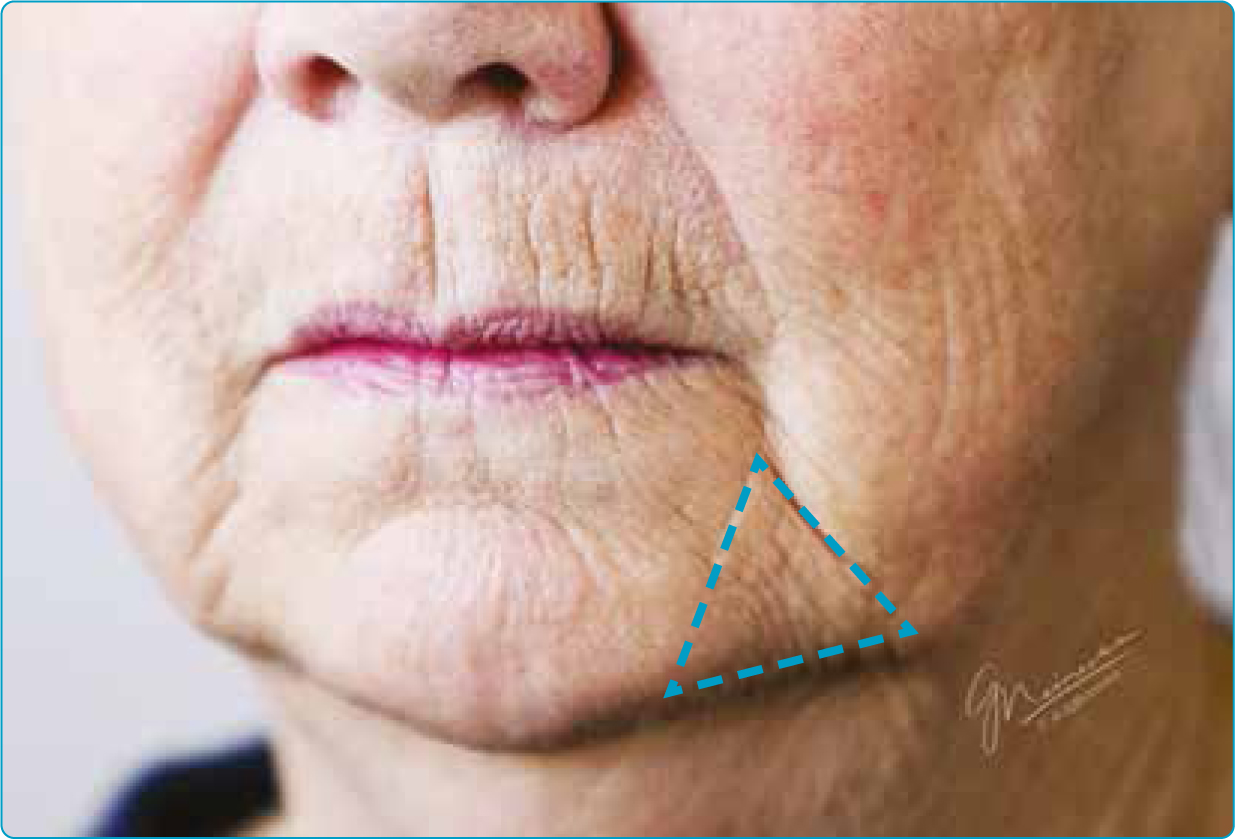

The area flanking the mental trigone is called the perimental zone. This region is medial to and includes the marionette lines. It is limited superiorly by the lower lip vermilion and ends inferiorly at the mandibular border. Here too, soft tissue sustains volumetric loss. Combined with bony support loss in the incisive fossa, the solitary mentalis muscle presents as an elevated golf ball-like tumescence [fig. 6].

With time, the smooth, full, uninterrupted contours of youth seem to disaggregate. The once-subtle transitions between anatomical facial segments are replaced by shadowy creases and an irregular, pock-marked surface emerges. Lines form at muscle origins while skin pores enlarge and become more conspicuous (Lee et al. 2022). These changes represent the hallmark of the senescent chin.

Injectable options for the chin

The approach to chin modifications with injectables is wholly predicated on the presenting deficiencies.

These deficiencies can be divided into two general categories:

- Projection and shape, or

- Projection and shape with age-related defects.

Projection and shape

A youthful under-projected chin should be evaluated to determine the magnitude of the projection deficiency as well as any associated geometric defects. Underprojection can result from either a bony or soft tissue insufficiency or it can be a combination of both. Geometric assessment should determine any disparities in width and overall shape. For example: is the chin too pointy? Overly square? Too narrow? Too short?

Viewed from the injectable modality standpoint, projection problems that are bony in origin require dermal filler to restore. Prior to placement of dermal filler in the central chin area, it is advantageous to treat the mentalis muscle with toxin. Decreasing muscle contractility prior to treatment, increases the residency time of the filler. Pretreatment with toxin also decreases potential flattening of the dermal filler projection within that first 48 postoperative hour window when hyaluronic acid-based fillers are still malleable.

Projection deficits that are muscular in origin and have satisfactory bony support can often be treated solely with neuromodulation. The mentalis muscle is very strong and can tolerate fairly high, well-placed doses of toxin without untoward effects and should be managed aggressively. Treating this muscle also decreases muscular traction on the lower lip, allowing a more neutral placement and fuller labial contour.

Projection and shape with age-related defects

Similar to the youthful chin, the senescent chin may present with size, shape and projection challenges. However, dimensional changes in the maturing chin are compounded by age-related distortions. A hyperactive mentalis muscle is virtually endemic with increasing age, therefore, treatment of the full constellation of presenting deficits is often best initiated with neuromodulation. Treatment with toxin decreases the baseline ‘tug’ the muscle applies to its skin insertions. This diminishes the characteristic ‘potato eye’ deformity. It produces a smoother, fuller appearance. Moreover, as the mentalis muscle also lifts the caudal aspect of the chin rostrally, treatment with neuromodulation decreases the appearance of the mental crease depth and width. By the same principle, toxin placed at the muscle origin site can increase the length of the chin in its rostral-caudal dimension. This sets the stage for the dermal filler segment of rejuvenation.

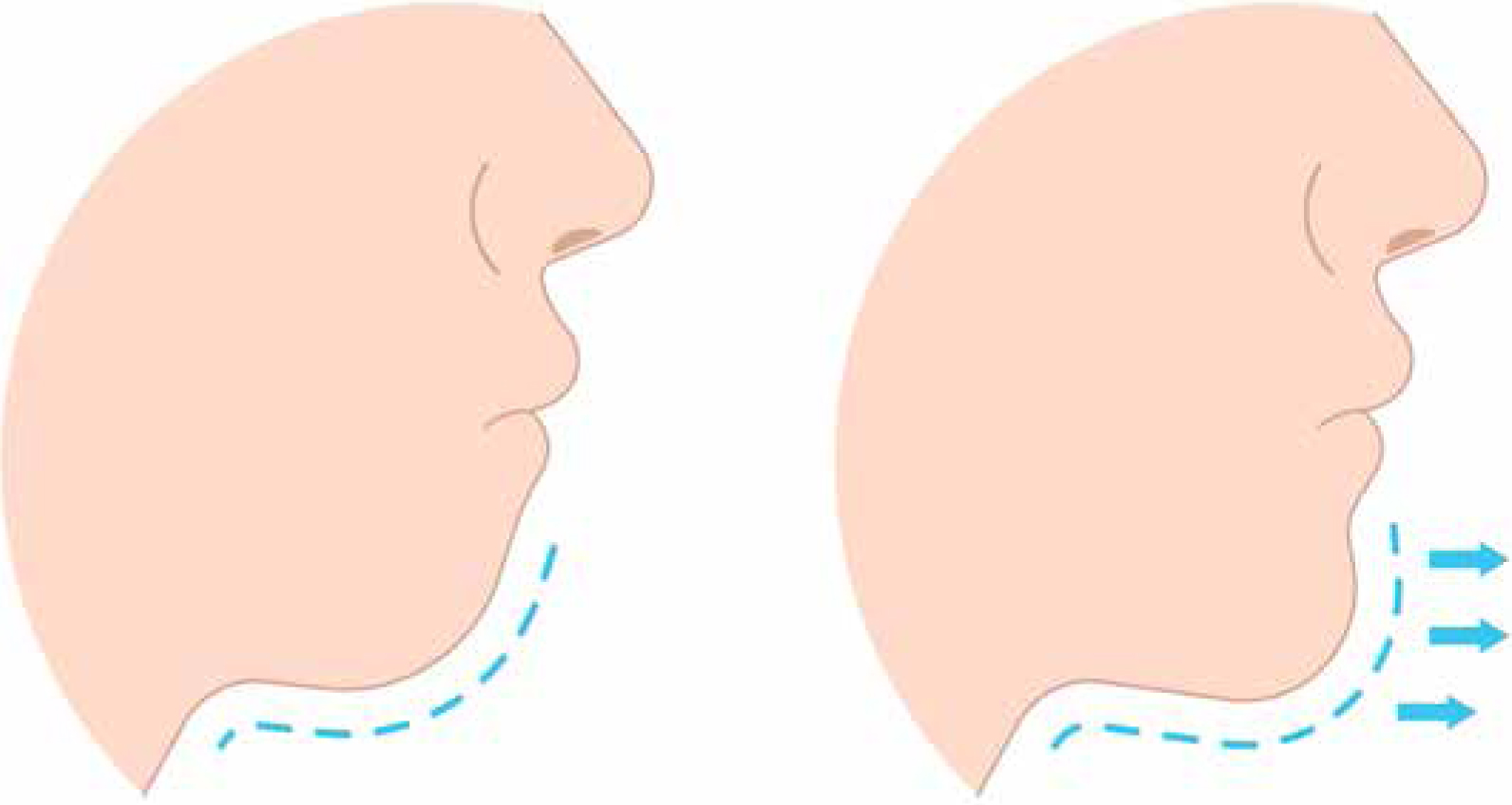

When the full effect of neuromodulation is realised, strategic placement of dermal filler can replace extant volume loss. Re-establishing maximum chin projection (pogonion) is an excellent starting point for any augmentation. Increasing chin prominence effectively provides a ‘tent pole’ that not only elevates the tissue immediately superficial to the filler, it suspends neighboring tissue as well. This aids in establishing a smoother mandibular line by distracting the adjacent ptotic tissue in the pre-jowl area. Once the pogonion is augmented to either: 1) coincide with the ‘zero-degree meridian line’ (a vertical line dropped from the soft tissue nasion perpendicular to the Frankfort Horizontal Plane), or 2) provide enough projection to achieve a satisfactory aesthetic endpoint, the prejowl area is treated next.

The prejowl sulcus typically presents as a triangular-shaped depression at the caudal end of the marionette line [fig.7]. Small aliquots of dermal filler placed strategically in this area are effective in masking the mandibular undulations associated with the aging chin. The youthful appearance of an unbroken line sweeping from pogonion to gonial angle can be recovered with surprisingly modest volumes in this area.

With the chin augmented and the mandibular sweep re-established, perimental hollows are the logical next step. These hollows form trapezoidal medial extensions of the marionette lines ending at the midline and superior to the mental crease [fig. 8]. Untreated, these present as shadowy recesses consistent with an aging visage. Replacing volume loss in the perimental zone evokes a more approximate depiction of a youthful lower facial third.

Summary

Before any injectable treatment, a thorough discussion of existing problem(s) and patient-desired outcomes should take place. Obtaining an accurate assessment of the patient's concept of expected results is time well spent.

This conversation should clarify four things:

- Specifically, what the patient hopes to achieve

- Whether injectables are the appropriate modality to achieve the desired result

- Whether the patient has reasonable expectations

- Whether you want to be the one who treats this patient.

Knowledge of the typical age-related deformities native to each area of the face helps streamline the approach to treatment planning. Moreover, when rejuvenating the chin, logical staging of injectable treatment can result in a longer duration of effect, more economical use of product, and potentially better aesthetic outcomes. Beginning with the end in mind when treating the chin, as well as all other facial injectable areas, establishes a blueprint for success.

Key points

- The article underscores the critical role of the chin in facial aesthetics, balance, and social perception, emphasising its significance in overall facial rejuvenation.

- Evolutionary perspectives on the human chin are explored, highlighting its uniqueness and the lack of consensus on its functional purpose.

- Age-related changes in the chin, both in bone and soft tissue, are discussed, presenting challenges like resorption, muscle-skin irregularities, and a ‘potato-eye’ appearance.

- The article outlines strategic approaches for injectable treatments, addressing projection and shape deficiencies in the chin, with considerations for age-related defects, while emphasising the importance of comprehensive treatment planning and patient communication.

CPD reflective questions

- In the context of the chin's role in social signaling and first impressions, how do you think cultural perceptions influence the ideals of chin aesthetics, and how might practitioners navigate these considerations?

- Reflect on the impact of aging on the chin, specifically the described soft tissue changes. How might these changes affect an individual's self-image, and how can practitioners address them through injectable treatments?

- The article emphasises the importance of a holistic approach to facial aesthetics, including the often overlooked chin. How can practitioners overcome the challenge of patient and industry focus on popular areas like lips and cheeks to ensure a more comprehensive treatment plan?

- Considering the need for thorough patient discussions, what strategies can practitioners employ to facilitate meaningful conversations about treatment goals, injectable options, and realistic expectations, particularly when addressing the chin?