References

Following a new technique for thread insertion

Abstract

Thread lifts are an increasingly prevalent non-surgical procedure. Dr Irfan Mian details a new technique that has promising indications for longer results and improved patient satisfaction, as well as the dangers that needles may bear

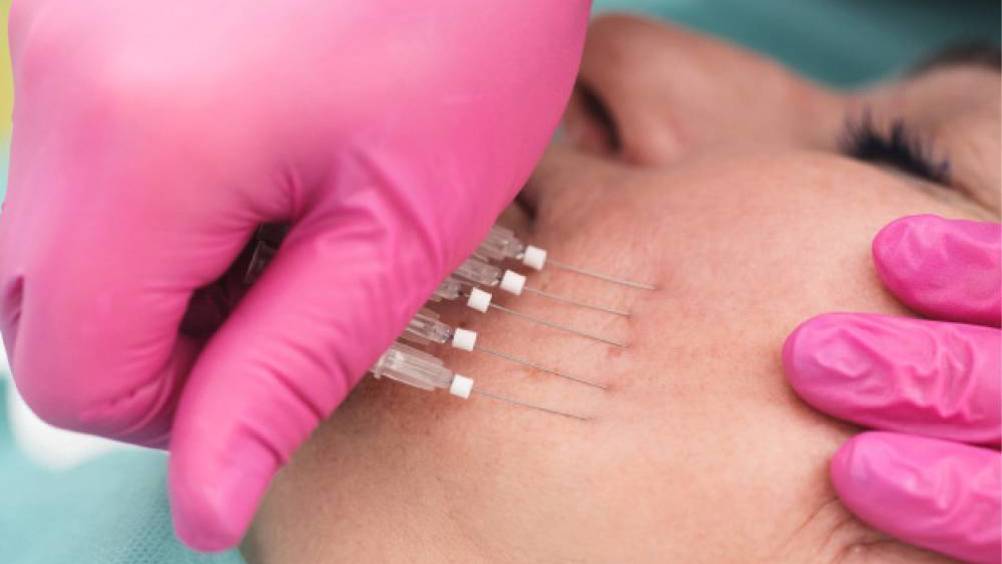

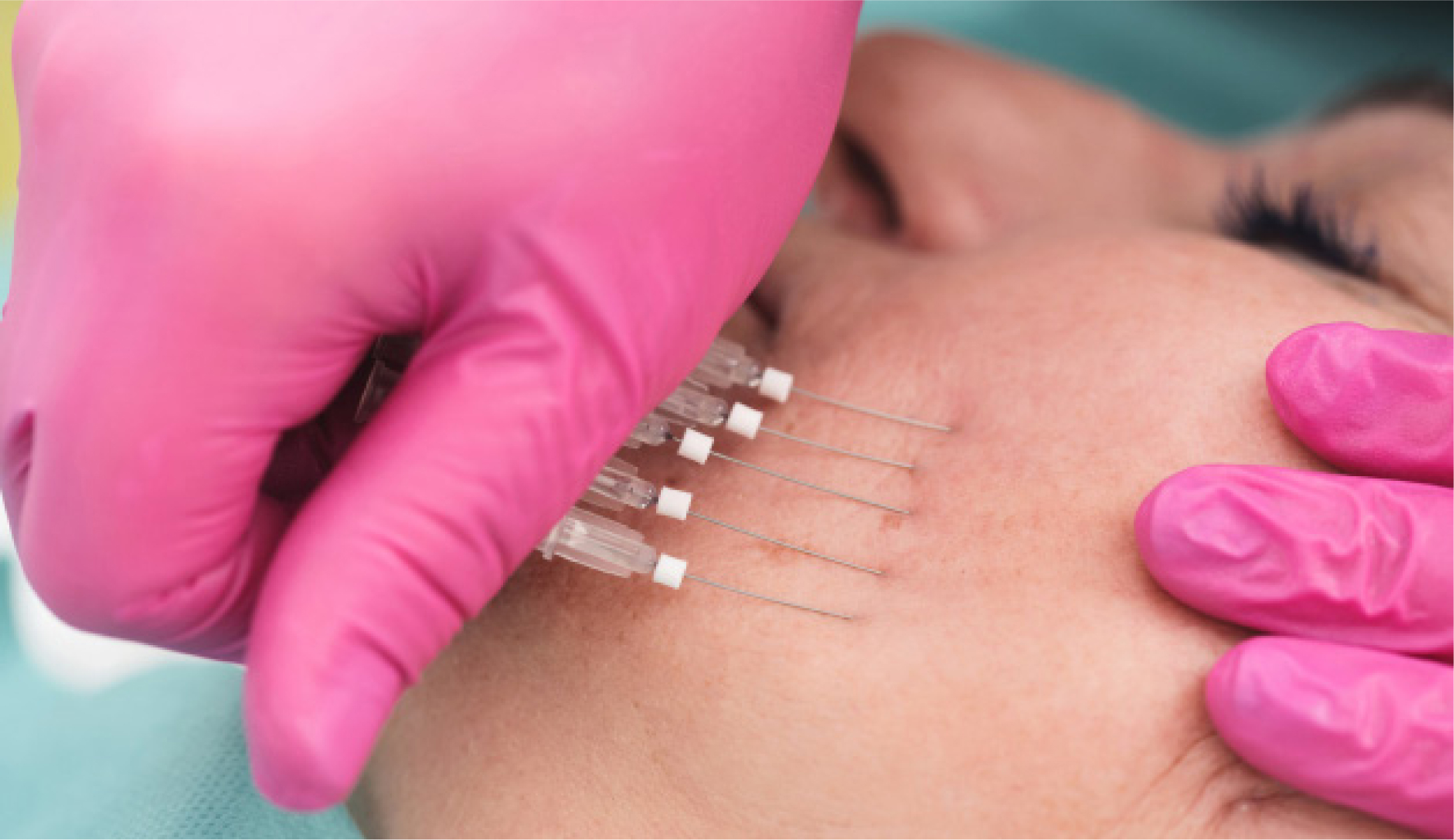

The thickness of the patient's skin is a critical factor in deciding whether a blunt cannula or needle PDO threads are to be used

The thickness of the patient's skin is a critical factor in deciding whether a blunt cannula or needle PDO threads are to be used

Medical aesthetics is a rapidly advancing field and is becoming increasingly popular with patients, many of whom are requesting non-surgical procedures.

In fact, new research shows that, while demand for surgery has decreased, especially after the ‘PIP’ breast implants scandal (Hegyi, 2019), non-surgical treatments are booming. This industry could be worth £3 billion by 2022 (Buisson, 2018).

The head, neck and other parts of the body are amenable to treatments, and results are very satisfactory when performed by properly trained, qualified and experienced medical aesthetic clinicians.

However, there is one part of the body that is difficult to treat, and yet, is the part that shows one's age to the world: the neck, which is an area usually not covered by clothing.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Journal of Aesthetic Nurses and reading some of our peer-reviewed resources for aesthetic nurses. To read more, please register today. You’ll enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

-

Limited access to clinical or professional articles

-

New content and clinical newsletter updates each month